This comprehensive guide explores the philosophy, principles and practice of Montessori education and its enduring relevance in 2025. From its historical origins to its modern application, discover why this child-centred approach continues to transform education worldwide by fostering independence, creativity and lifelong learning skills.

Origin of Montessori Education

The Montessori method emerged from the pioneering work of Dr. Maria Montessori, who made history as Italy’s first female physician. In 1907, she established her initial ‘Children’s House’ (Casa dei Bambini) in a disadvantaged area of Rome, creating what would become one of the most influential educational approaches of the modern era.

Dr. Montessori’s method wasn’t developed through abstract theory but through meticulous scientific observation of how children naturally learn. Working with children in Rome’s impoverished San Lorenzo district, she documented their remarkable capacity for concentration, self-discipline and joyful learning when provided with the right environment and materials. These observations formed the empirical foundation of the Montessori approach, which represented a radical departure from the rigid, teacher-centred education prevalent at the time.

From these humble beginnings in a single Roman classroom, Montessori education has experienced extraordinary global expansion. By 2025, the methodology has been embraced across cultural, economic and geographic boundaries, with over 20,000 Montessori schools operating worldwide. This remarkable growth reflects the approach’s adaptability and universal appeal—spanning six continents and diverse educational contexts from early childhood centres to secondary schools, in both public and private sectors.

Maria Montessori: Visionary Educator

Dr. Maria Montessori (1870-1952) was a truly revolutionary figure whose pioneering work transcended the boundaries of education to encompass medicine, anthropology, and social reform. As Italy’s first female physician during an era when women’s professional opportunities were severely restricted, she brought a unique scientific rigour to the field of education. Her background in medicine informed her meticulous approach to observing children’s development and learning patterns, establishing a methodology grounded in empirical evidence rather than prevailing educational theories.

At the heart of Montessori’s vision was a profound respect for the child as a complete human being with inherent dignity and potential. She recognised that children are not empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, but active participants in their own development with an innate drive to learn. This child-centred perspective represented a dramatic shift from the authoritarian educational models of her time. She emphasised that education should nurture the whole child—intellectually, physically, emotionally, and socially—rather than focusing exclusively on academic content.

Montessori’s educational philosophy was characterised by a delicate balance between freedom and structure. She advocated for children’s independence and self-direction while simultaneously recognising the importance of an ordered environment and appropriate guidance. Her approach emphasised the development of self-discipline through meaningful activity rather than through external rewards and punishments. This vision of education as a path to both personal fulfillment and social harmony continues to resonate with educators and parents in 2025, as we recognise the importance of nurturing autonomous, capable individuals prepared to navigate an increasingly complex world.

Montessori’s Foundational Philosophy

The Montessori approach is built upon a revolutionary conception of childhood and learning that remains transformative in 2025. At its foundation is the recognition that children are not passive recipients of knowledge, but active, capable participants in their own education. Dr. Montessori observed that children possess a natural curiosity and drive to engage with their environment, to understand the world around them, and to develop independence. This insight shifted the educational paradigm from teacher-centred instruction to a model that harnesses and supports the child’s intrinsic motivation to learn.

Central to Montessori philosophy is the conviction that every child harbours enormous potential that education should nurture rather than constrain. Dr. Montessori famously stated, “The child is both a hope and a promise for mankind.” This perspective views education not merely as the transmission of information, but as the cultivation of human potential in its fullest sense—intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual. The teacher’s role is transformed from an authority figure delivering knowledge to a guide who removes obstacles to the child’s natural development and provides resources for exploration and discovery.

Montessori philosophy explicitly rejects traditional educational practices based on rote memorisation, standardisation, and extrinsic rewards. Instead, it embraces a model where children engage in meaningful activities that correspond to their developmental needs and interests. Learning occurs through hands-on exploration, discovery, and the mastery of increasingly complex skills and concepts. This approach fosters deep understanding rather than superficial knowledge, developing learners who understand the why behind the what. The continued relevance of these principles in 2025 speaks to their timeless insight into how humans naturally learn and develop.

Child as Active Learner

Children are viewed as capable, self-motivated learners who actively construct their own knowledge through exploration and discovery

Development of Human Potential

Education aims to nurture each child’s unique gifts and capabilities, supporting their intellectual, physical, emotional and social development

Learning Through Discovery

Knowledge is acquired through hands-on experience, exploration, and the mastery of increasingly complex concepts and skills

Five Core Principles of Montessori

The Montessori methodology is structured around five interconnected principles that provide the theoretical foundation for its distinctive approach to education. These principles, derived from Dr. Montessori’s scientific observations of child development, continue to guide Montessori practice worldwide in 2025, offering a coherent framework for understanding how children learn and develop.

Respect for the Child

Recognising each child’s innate dignity, unique potential, and individual developmental trajectory. This principle underpins all aspects of Montessori practice, from classroom design to teacher-child interactions.

The Absorbent Mind

Acknowledging children’s extraordinary capacity to unconsciously absorb information from their environment, particularly in the first six years of life when the foundations for language, culture, and personality are established.

Sensitive Periods

Identifying windows of heightened receptivity to particular types of learning and development, during which children can acquire specific skills and knowledge with greater ease and enthusiasm.

Prepared Environment

Creating a carefully designed, ordered space that facilitates independent learning, provides appropriate challenges, and responds to children’s developmental needs and interests.

Auto-education

Enabling self-directed learning through specially designed materials, freedom of choice, and opportunities for independent work, allowing children to develop concentration, self-discipline, and intrinsic motivation.

These five principles work in harmony to create an educational approach that respects children’s natural development while providing the structure and support they need to flourish. In Montessori classrooms worldwide, these principles inform daily practice, from the arrangement of materials to the way teachers interact with students. They provide a coherent theoretical framework that distinguishes Montessori education from other approaches and explains its enduring effectiveness in supporting children’s holistic development.

Respect for the Child

Respect for the child represents the philosophical cornerstone of the Montessori approach, permeating every aspect of its educational practice. This principle goes far beyond mere politeness or consideration; it embodies a profound recognition of each child’s inherent dignity and worth as a complete human being. In Montessori environments, children are not viewed as incomplete adults or empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, but as unique individuals with their own strengths, interests, and developmental timelines.

This respect manifests in the acknowledgment that each child has their own path and pace of development. Montessori education rejects one-size-fits-all approaches, instead embracing the diversity of human development. Children are allowed to progress according to their individual readiness rather than arbitrary age-based expectations. This individualised approach honours the child’s natural development and prevents the frustration and disengagement that can occur when children are pushed beyond their developmental capabilities or held back from pursuing their interests.

The principle of respect fundamentally transforms the role of the teacher in the educational process. Rather than acting as an authoritarian figure who directs and controls children’s learning, the Montessori teacher serves as a guide who observes carefully, provides appropriate support, and creates conditions for self-directed learning. This shift in the power dynamic between adult and child fosters an atmosphere of mutual respect where children develop authentic self-confidence and a sense of agency. By experiencing respect themselves, children learn to respect others, creating a foundation for positive social interaction and community.

In 2025, this emphasis on respect for the child resonates strongly with contemporary understanding of children’s rights and developmental psychology. Research continues to confirm that children thrive in environments where they feel respected and valued, developing stronger intrinsic motivation, self-regulation, and emotional well-being. The Montessori principle of respect provides a powerful antidote to educational approaches that prioritise standardisation and compliance over individual development and dignity.

The Absorbent Mind

The concept of the absorbent mind represents one of Dr. Montessori’s most profound insights into child development and forms a critical foundation of her educational approach. Through careful observation, she recognised that young children possess an extraordinary capacity to absorb information, language, cultural practices, and skills from their environment—not through conscious effort or deliberate study, but unconsciously and effortlessly, simply through living and interacting with their surroundings.

Dr. Montessori identified two distinct phases of the absorbent mind. From birth to approximately three years of age, children experience the “unconscious absorbent mind,” where they take in impressions from their environment without conscious awareness or effort. During this period, children acquire their native language, cultural norms, and fundamental movement patterns without formal instruction. From ages three to six, children transition to the “conscious absorbent mind,” where they continue to absorb readily from their environment but begin to direct their learning more intentionally, developing greater awareness of their own learning processes.

The educational implications of the absorbent mind are profound. Montessori environments for young children are designed to provide rich, carefully prepared experiences that capitalise on this unique learning capacity. Every detail of the classroom—from the quality of language used to the precision of materials presented—is considered with the knowledge that children will absorb these elements into their developing minds. This period represents a crucial opportunity to establish foundations for language development, mathematical thinking, cultural understanding, sensory refinement, and social interaction.

In 2025, neuroscience continues to validate Montessori’s observations about the absorbent mind, with research confirming the extraordinary neuroplasticity of the young brain and the critical importance of early experiences in shaping neural pathways. Contemporary understanding of brain development has only strengthened appreciation for Montessori’s insight that the first six years of life represent a period of unparalleled learning potential that should be supported with carefully designed environments rather than left to chance.

Sensitive Periods for Learning

Sensitive periods represent a cornerstone of Montessori developmental theory, describing distinct phases when children display heightened interest and aptitude for acquiring specific skills or knowledge. Dr. Montessori observed that during these periods, children demonstrate an almost irresistible drive to engage with particular aspects of their environment, absorbing related concepts and skills with remarkable ease, concentration, and joy. Unlike conventional educational timetables based on chronological age, Montessori education is structured to respond to these natural developmental windows.

Montessori identified several key sensitive periods that typically unfold during the first six years of life. The sensitive period for order emerges in early toddlerhood, when children crave consistency and predictability in their physical environment. The sensitive period for language spans the first six years, peaking around age 2-3 when vocabulary acquisition accelerates dramatically. Movement, particularly the refinement of fine motor skills, has a sensitive period from birth to around age 4. Other notable sensitive periods include sensorial exploration (0-5 years), interest in small objects (1-4 years), and social relations (2.5-6 years). During each of these periods, children learn the corresponding skills with greater efficiency and enthusiasm than at any other time in development.

Language (0-6 years)

Heightened receptivity to language patterns, vocabulary, and communication structures

Movement (0-4 years)

Refinement of both gross and fine motor coordination and precision

Order (1-3 years)

Strong desire for consistency, routine, and logical organization in the environment

Social Relations (2.5-6 years)

Increased interest in social interactions, manners, and cultural norms

Montessori environments are carefully designed to respond to these sensitive periods by providing appropriate materials and activities that correspond to children’s developmental readiness. Teachers are trained to recognise signs of emerging sensitive periods through careful observation, then introduce materials that satisfy the corresponding developmental need. This responsive approach stands in stark contrast to standardised curriculum sequences that expect all children to develop the same skills at the same time. By 2025, advances in developmental neuroscience have further validated Montessori’s insights, confirming that brain development indeed follows predictable sequences with periods of heightened neuroplasticity for specific functions.

The Prepared Environment

The prepared environment stands as one of the most distinctive and essential elements of Montessori education. Far more than just a physical space, it represents a carefully designed learning ecosystem that responds to children’s developmental needs while promoting independence, concentration, and joyful discovery. Dr. Montessori recognised that the environment itself serves as a teacher, directly influencing children’s behaviour, engagement, and learning. Every aspect of a Montessori classroom is therefore thoughtfully arranged to support optimal development.

Physical characteristics of the prepared environment include child-sized furniture that allows children to move and work comfortably without adult assistance. Materials are displayed on open, accessible shelves at children’s eye level, inviting exploration and independent selection. The space is characterised by order and beauty, with a place for everything and everything in its place. Natural light, plants, and artwork create an atmosphere of warmth and aesthetic appreciation. The environment is divided into distinct curriculum areas—practical life, sensorial, language, mathematics, cultural studies—each with its own sequenced materials that progress from simple to complex, concrete to abstract.

Beyond its physical attributes, the prepared environment encompasses a carefully maintained social and emotional atmosphere. Clear, consistent boundaries establish expectations for respectful behaviour and care of materials. A mixed-age grouping (typically spanning three years) creates a mini-society where children learn from peers and develop leadership skills. Freedom within limits allows children to choose their activities while developing self-discipline and responsibility. The teacher’s role involves preparing and maintaining this environment, observing children’s interactions with it, and making adjustments based on their evolving needs.

In 2025, the concept of the prepared environment continues to distinguish Montessori education from conventional classrooms. While many educational approaches now incorporate elements such as learning centres or student choice, the Montessori prepared environment remains unique in its comprehensive design, scientific foundation, and meticulous attention to developmental appropriateness. Research increasingly confirms the impact of physical environments on learning outcomes, validating Montessori’s pioneering emphasis on space as a critical educational component.

Auto-Education: Learning by Doing

Auto-education—the concept that children can educate themselves through purposeful interaction with the environment—represents one of Montessori education’s most revolutionary principles. This approach rejects the traditional model where knowledge is transmitted from teacher to student, instead recognising children’s innate capacity to construct their own understanding through hands-on exploration and discovery. Dr. Montessori observed that when provided with appropriate materials in a supportive environment, children naturally engage in activities that develop their intellect, refine their movements, and build their independence.

Central to auto-education is the child’s freedom to choose activities based on their interests and developmental needs. In Montessori classrooms, children select their work from available materials, determine how long to engage with each activity, and work at their own pace without arbitrary interruptions. This freedom of choice fosters intrinsic motivation—children work not for external rewards or adult approval, but for the satisfaction of mastery and discovery. Through repeated cycles of choosing, concentrating, and completing activities, children develop self-discipline, focus, and a sense of accomplishment that fuels further learning.

Montessori materials are specifically designed to facilitate auto-education through built-in “control of error” features that allow children to assess and correct their own work without adult intervention. For example, knobbed cylinders that only fit correctly in matching holes, or colour tablets that must be arranged in precise gradation. These self-correcting qualities enable children to identify and fix mistakes independently, developing problem-solving skills and resilience while reducing dependence on adult validation. The teacher observes this process carefully, intervening only when necessary and always with the goal of fostering greater independence.

Independent Choice

Child selects activity based on interest and readiness

Concentrated Engagement

Deep focus and hands-on interaction with materials

Self-Assessment

Recognition and correction of errors through material design

Mastery & Satisfaction

Completion leading to confidence and readiness for new challenges

By 2025, the principle of auto-education has gained increased recognition as research in cognitive science confirms the effectiveness of active, self-directed learning in developing deep understanding and transferable skills. In a world where information is readily available but the ability to think critically and learn independently is increasingly valuable, Montessori’s emphasis on auto-education provides children with essential tools for lifelong learning and adaptation.

Montessori Classroom in Practice

Stepping into a Montessori classroom reveals an environment distinctly different from conventional educational settings. The most immediately noticeable feature is the bustling, purposeful activity—children working independently or in small groups, moving freely throughout the space, engaged in diverse tasks from mathematical operations to practical skills like food preparation. Unlike traditional classrooms where all students typically work on the same subject simultaneously, the Montessori environment supports multiple activities concurrently, allowing each child to follow their interests and developmental needs.

A defining characteristic of Montessori classrooms is the mixed-age grouping, typically spanning three years (3-6, 6-9, 9-12 years). This arrangement creates a microcosm of society where younger children learn from observing more experienced peers, while older children reinforce their knowledge by teaching younger classmates. The diversity of ages and abilities fosters collaboration rather than competition, with children supporting one another’s learning. This multi-age structure allows for continuity of relationships, as children typically remain with the same teacher for three years, building deep connections and allowing educators to develop thorough understanding of each child’s learning style and needs.

The Montessori teacher functions quite differently from a traditional instructor. Rather than standing at the front of the room delivering lessons to the whole group, the Montessori teacher moves throughout the classroom, presenting individual or small-group lessons based on careful observation of children’s readiness. The teacher’s primary role involves connecting children with appropriate materials, observing their work to assess understanding and development, and maintaining the prepared environment. This approach requires extensive training in observational techniques, precise presentation of materials, and the ability to support without interfering with children’s concentration and independence.

The phrase “freedom within limits” aptly describes the carefully balanced structure of Montessori classrooms. Children enjoy considerable liberty to choose activities, work partners, and work spaces, but within a framework of clear expectations regarding responsible use of materials, respect for others’ work, and completion of tasks. This balance fosters self-regulation and internal discipline rather than reliance on external controls. By 2025, the effectiveness of this approach in developing executive function skills—increasingly recognised as crucial for academic and life success—has contributed to the growing adoption of Montessori principles in diverse educational settings worldwide.

Montessori Materials & Activities

The specialised materials developed by Dr. Montessori represent one of the most distinctive and scientifically designed aspects of the Montessori approach. Far from random educational toys, these materials embody concrete representations of abstract concepts, carefully sequenced to build understanding progressively from simple to complex, concrete to abstract. Each material isolates a single quality or concept—such as size, weight, colour, or mathematical quantity—allowing children to focus their attention and develop clear understanding before combining concepts. Materials are designed with aesthetic appeal, using natural materials like wood and glass whenever possible, inviting children’s interest and careful handling.

Montessori materials are organised into several interconnected curriculum areas. Practical Life materials develop independence, concentration, and coordination through everyday activities like pouring, buttoning, and food preparation. Sensorial materials refine the senses and build vocabulary through exploration of dimensions, shapes, colours, textures, sounds, and smells. Language materials progress from phonetic awareness to writing and reading through hands-on activities with sandpaper letters, movable alphabets, and carefully sequenced reading materials. Mathematics materials make abstract concepts tangible through manipulatives that allow children to literally hold and manipulate quantities, visualising operations like addition and multiplication. Cultural materials introduce geography, science, history, and the arts through concrete, interactive experiences.

A distinctive feature of Montessori materials is their self-correcting design, which enables children to recognise and correct their own errors without adult intervention. This built-in “control of error” might be visual (pieces fit together only when correctly matched), physical (pieces won’t fit if incorrectly placed), or logical (the work produces an unexpected result when done incorrectly). This design fosters independence, problem-solving skills, and confidence while reducing reliance on external validation. The sequencing of materials creates an integrated curriculum where concepts build upon one another, forming a coherent progression from concrete experiences to abstract understanding. By 2025, neuroscience research has increasingly validated Montessori’s intuitive understanding of how multisensory, hands-on learning experiences effectively build neural pathways and support cognitive development.

Play-Based and Practical Learning

Montessori education offers a unique perspective on play and its relationship to learning, one that transcends the traditional play-versus-work dichotomy often found in educational discussions. Rather than separating play from learning, Montessori environments integrate purposeful activity, creativity, and joy in ways that engage children’s natural curiosity and developmental drives. Dr. Montessori observed that children find deep satisfaction in activities that develop their capabilities and connect them to the real world, challenging the assumption that “educational” activities must be separate from those that children find enjoyable and fulfilling.

Practical life activities form a cornerstone of the Montessori approach, particularly in early childhood classrooms. These activities—such as food preparation, table washing, plant care, and clothing fastening—address children’s natural interest in participating in the “real work” they observe adults performing. Through practical life exercises, children develop independence, coordination, concentration, and order while gaining tangible life skills. A three-year-old carefully polishing a mirror, a four-year-old preparing fruit for snack time, or a five-year-old sewing a button experiences the satisfaction of meaningful contribution while refining movements and building confidence. These activities, while educational in purpose, engage children’s natural playfulness and creativity.

The integration of practical, purposeful activities distinguishes Montessori’s approach from both academic-focused programs that prioritise direct instruction and purely play-based programs without structured learning components. Montessori environments strike a balance where children’s natural activity drives development, but within a carefully prepared environment offering activities aligned with developmental needs. This approach recognises that children’s play naturally evolves toward increasing purpose and reality-orientation as they mature, and that meaningful contribution to their community fulfills deep psychological needs.

By 2025, the Montessori approach to integrated play and purposeful activity has gained increased recognition as research confirms the developmental benefits of hands-on, meaningful engagement. As educational systems worldwide reconsider the role of play in learning, Montessori’s century-old insight that children naturally seek purposeful activity that develops their capabilities offers a model that respects both children’s need for joyful engagement and their drive toward competence and contribution.

Evidence of Montessori Outcomes

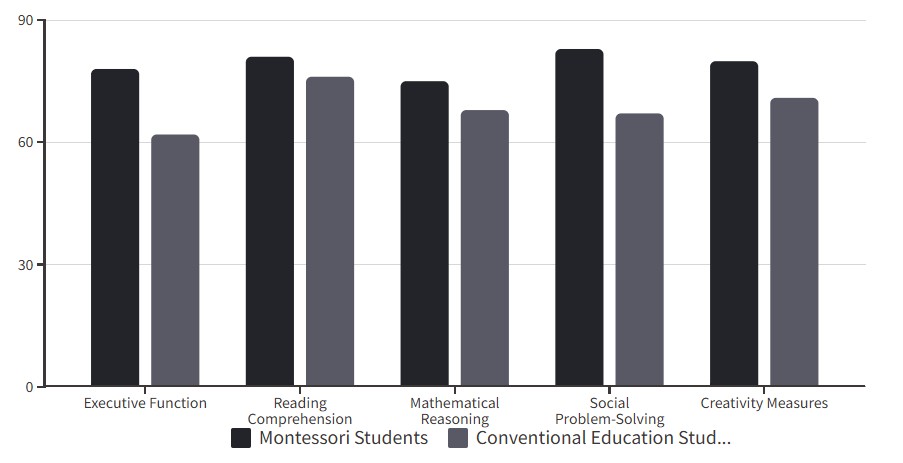

As Montessori education has expanded globally, a substantial body of research has emerged examining its effectiveness across various domains of child development. Studies conducted through 2025 consistently demonstrate that quality Montessori implementation is associated with positive outcomes in academic achievement, social-emotional development, and executive functioning. These findings have contributed to growing recognition of Montessori education as an evidence-based approach rather than simply an alternative philosophical model.

In academic domains, longitudinal research has documented Montessori students’ strong performance in core subjects. Studies comparing Montessori and non-Montessori students have found that Montessori children typically demonstrate comparable or superior outcomes in reading and mathematics, often showing particular strengths in mathematical reasoning and complex problem-solving. Research published in prestigious journals has documented that children from authentic Montessori programs show accelerated progress in reading during primary years, stronger narrative skills, and more sophisticated approaches to mathematical thinking. Importantly, these academic benefits have been observed across diverse socioeconomic populations, suggesting Montessori’s potential as an equalising educational approach.

Beyond academic metrics, research has documented Montessori education’s impact on critical non-cognitive skills. Multiple studies have found enhanced executive function—including working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control—among Montessori students compared to peers in conventional programs. Social-emotional outcomes also show positive patterns, with research indicating that Montessori children typically demonstrate greater social cognition, stronger conflict resolution skills, and more sophisticated understanding of fairness and justice concepts. Several studies have noted Montessori students’ heightened intrinsic motivation, with greater focus on learning for mastery rather than external rewards.

Long-term follow-up studies have provided compelling evidence for Montessori education’s enduring impact. Research tracking Montessori graduates through secondary school and beyond has documented sustained advantages in academic achievement, intrinsic motivation, and social adjustment. A significant 2023 study following children from early childhood through university found that longer exposure to quality Montessori education predicted stronger academic performance, greater creativity, and higher levels of well-being in young adulthood. While research continues to evolve, the accumulating evidence suggests that Montessori education provides children with both immediate benefits and lasting advantages for lifelong learning and development.

Montessori vs. Traditional Education

Understanding the distinctive characteristics of Montessori education often becomes clearer when contrasted with conventional educational approaches. While educational systems worldwide exhibit considerable variation, several fundamental differences distinguish Montessori methodology from traditional education, reflecting their divergent philosophical foundations and practical implementations. These contrasts help explain why Montessori offers a substantially different learning experience despite addressing similar academic content.

| Feature | Montessori | Traditional |

| Learning Style | Self-directed exploration with teacher guidance; children choose activities based on interest and readiness | Teacher-led instruction following predetermined curriculum sequence; whole-class lessons with standardised pacing |

| Assessment | Continuous observation and documentation of process and mastery; detailed narrative reporting; minimal standardised testing | Periodic testing and grading; emphasis on product over process; standardised assessments to measure achievement |

| Class Structure | Mixed-age groupings spanning 3 years; children remain with same teacher for multiple years; collaborative community | Single-age groupings; annual teacher changes; often emphasises individual achievement and competition |

| Materials | Specialised, self-correcting materials that isolate concepts; hands-on, multisensory learning tools; progression from concrete to abstract | Textbooks, worksheets, and digital resources; often abstract presentations of concepts; limited hands-on materials |

| Teacher Role | Guide and facilitator who observes, presents materials, and supports independent learning; rarely addresses whole group | Instructor who delivers information, manages behaviour, and evaluates work; often teaches to whole group simultaneously |

| Curriculum Approach | Integrated curriculum connecting subjects; follows child’s interests; deep exploration of topics; no artificial time constraints | Segmented subjects with distinct time blocks; predetermined topics regardless of interest; coverage often prioritised over depth |

| Motivation | Emphasis on intrinsic motivation; joy of discovery and mastery; absence of external rewards, grades, or punishments | Often relies on extrinsic motivators; grades, rewards, recognition systems; external validation emphasised |

These contrasts reflect fundamentally different views of the child and the learning process. Traditional education often operates from an efficiency model focused on standardised knowledge transmission, while Montessori prioritises individual development and intrinsic motivation. The Montessori approach emphasises student agency, hands-on exploration, and the development of executive function skills alongside academic content. Traditional systems typically maintain greater adult control over learning processes, with more abstract presentation of concepts and externally imposed structure.

It’s important to note that these distinctions represent general patterns rather than absolute categories. By 2025, many conventional schools have incorporated elements inspired by Montessori and other progressive approaches, including learning centres, project-based learning, and increased student choice. Similarly, Montessori schools vary in their implementation fidelity, with some adapting aspects of the approach to align with local educational requirements or community needs. Nevertheless, these foundational differences in philosophy and practice continue to distinguish authentic Montessori education from most conventional educational models.

Montessori’s Global Reach in 2025

By 2025, Montessori education has established a remarkable global presence, expanding far beyond its Italian origins to become one of the world’s most widely implemented alternative educational approaches. With over 20,000 Montessori schools operating across six continents, the methodology has demonstrated extraordinary cultural adaptability whilst maintaining its core principles. This global expansion reflects both increased recognition of Montessori’s effectiveness and growing demand for educational approaches that foster independence, creativity, and intrinsic motivation.

The distribution of Montessori schools varies considerably by region and educational sector. North America hosts the largest concentration, with approximately 5,000 schools in the United States alone, ranging from private institutions to public Montessori programmes serving diverse socioeconomic communities. Europe maintains strong Montessori representation, particularly in the Netherlands, Germany, and the United Kingdom, where Montessori principles have influenced mainstream educational policy. Asia has experienced the most rapid growth in recent years, with significant expansion in India, China, Japan, and South Korea, where Montessori’s emphasis on independence and creativity has resonated with educational reformers seeking alternatives to test-focused systems.

While traditionally strongest in early childhood education (ages 3-6), Montessori has expanded significantly into primary and secondary education by 2025. Over 40% of Montessori schools now offer elementary programmes (ages 6-12), with growing numbers extending through adolescence. Montessori secondary schools, though still less common, have increased substantially, developing innovative approaches that apply Montessori principles to adolescent development through project-based learning, entrepreneurship, and community engagement. Additionally, Montessori principles have been adapted for other populations, including toddler programmes, dementia care, and special education settings, demonstrating the methodology’s flexibility and broad applicability.

The Montessori approach has gained increased institutional recognition by 2025, with more countries incorporating Montessori-inspired elements into national educational standards and teacher training programmes. International organisations like UNESCO have acknowledged Montessori’s alignment with global educational goals emphasising critical thinking, creativity, and sustainable development. This mainstream acceptance represents a significant evolution from Montessori’s earlier position as a niche alternative, reflecting growing scientific validation of its developmental approach and recognition of its relevance to contemporary educational challenges.

Why Montessori Matters Today

In an era of rapid technological advancement and social change, Montessori education offers a particularly relevant approach to preparing children for an unpredictable future. As automation and artificial intelligence transform economies and workplaces, the skills that will remain uniquely human—creativity, complex problem-solving, emotional intelligence, and adaptability—align remarkably well with the capabilities Montessori education has emphasised for over a century. The Montessori focus on developing independent thinking, intrinsic motivation, and self-regulation provides children with the foundational skills to navigate a world where information is abundant but the ability to think critically about that information is increasingly precious.

Montessori education fosters lifelong learning dispositions that have become essential in contemporary society. In a world where knowledge rapidly becomes obsolete and careers evolve continuously, the ability to learn independently throughout life has unprecedented value. Montessori’s emphasis on curiosity, initiative, and self-directed learning cultivates precisely these qualities. Children in Montessori environments develop comfort with seeking answers to their own questions, persisting through challenges, and approaching new situations with confidence. These habits of mind support ongoing learning and adaptation far beyond formal education, preparing individuals for careers that may not yet exist and challenges that cannot yet be anticipated.

Global Citizenship

Montessori education cultivates respect for cultural diversity and environmental stewardship from an early age. Children develop a sense of connection to humanity and the natural world through concrete experiences with geography, biology, history, and culture. This foundation supports the development of engaged global citizens prepared to address complex international challenges.

Emotional Intelligence

As technological advancement accelerates, uniquely human capacities for empathy, collaboration, and ethical reasoning become increasingly valuable. Montessori’s mixed-age classrooms and emphasis on grace and courtesy provide daily opportunities to develop these social-emotional skills through authentic community participation rather than isolated lessons.

Entrepreneurial Mindset

Montessori education nurtures qualities essential for innovation and entrepreneurship: creative problem-solving, comfort with calculated risk, persistence through failure, and self-directed initiative. These characteristics prepare individuals to create value in an economy increasingly centred on innovation rather than standardisation.

Perhaps most fundamentally, Montessori education matters today because it honours children’s humanity in an age of increasing digitisation and standardisation. While many educational approaches focus narrowly on academic content delivery or technological literacy, Montessori addresses the development of the whole person—intellectual, physical, emotional, social, and spiritual. This comprehensive approach recognises that technological skills without ethical grounding, factual knowledge without critical thinking, or academic achievement without personal fulfillment leave individuals ill-equipped for meaningful participation in society. By focusing on human development in its fullest sense, Montessori education prepares not just future workers but future citizens, leaders, and fulfilled human beings.

Montessori and Modern Education Trends

As education systems worldwide grapple with preparing students for a rapidly evolving future, many contemporary educational trends show remarkable alignment with principles that Montessori education has embraced for over a century. This convergence highlights Montessori’s prescience and enduring relevance, as mainstream education increasingly adopts approaches that Montessori practitioners have long implemented. The growing emphasis on 21st-century skills—critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and communication—mirrors capabilities that Montessori environments have systematically cultivated through their integrated curriculum, hands-on materials, and collaborative classroom communities.

Personalised learning has emerged as a significant educational movement, with schools and technology platforms attempting to tailor education to individual students’ needs, interests, and learning pace. This approach, now facilitated by sophisticated educational technology, echoes Montessori’s longstanding practice of individualised learning paths. In Montessori classrooms, children progress according to their readiness rather than age-based expectations, with teachers keeping detailed records of each child’s development and presenting new materials when previous concepts have been mastered. This individualised progression, combined with choice based on interest, creates naturally differentiated learning experiences without requiring technological intervention.

The growing recognition of executive function skills as critical for academic and life success represents another area where contemporary research aligns with Montessori practice. Executive functions—including working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control—develop through experiences that require planning, sustained attention, and self-regulation. Montessori activities, with their emphasis on sequential steps, completion of cycles, and sustained concentration, provide ideal conditions for developing these capabilities. The freedom within limits characteristic of Montessori environments offers children regular opportunities to make choices, manage time, and regulate behaviour—precisely the experiences that research now confirms build executive function.

Competency-Based Education

Focus on mastery rather than time spent

Personalised Learning

Tailoring education to individual needs

Executive Function Development

Building cognitive control and self-regulation

Social-Emotional Learning

Integrating emotional intelligence with academics

Increased attention to social-emotional learning and mental health represents another area where educational trends have moved toward Montessori’s holistic approach. As schools worldwide incorporate explicit instruction in emotional awareness, relationship skills, and stress management, Montessori’s integrated approach to social-emotional development through community living offers a well-established model. Montessori environments address these dimensions not through isolated lessons but through daily experiences with conflict resolution, community responsibility, and emotional regulation. By 2025, this comprehensive approach to well-being has gained increased recognition as mental health concerns among young people have prompted educational systems to look beyond academic measures to consider how educational environments affect overall development and psychological health.

Challenges and Critiques

Despite its documented benefits and growing popularity, Montessori education faces several significant challenges that have limited its more widespread adoption and influenced public perception. Perhaps the most persistent barrier has been accessibility, particularly regarding economic factors. The substantial cost of authentic Montessori materials, specialised teacher training, and maintaining appropriate student-teacher ratios has traditionally made Montessori education more expensive to implement than conventional approaches. Consequently, private Montessori schools often charge tuition fees that place them beyond the reach of many families, creating a perception that Montessori is primarily for privileged communities. This accessibility challenge contradicts Dr. Montessori’s original work with children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and her vision of education as a path to social transformation.

The quality and consistency of Montessori implementation represents another significant challenge. Unlike regulated terms such as “chartered accountant” or “registered nurse,” the name “Montessori” is not legally protected in most jurisdictions, allowing any educational program to use the designation regardless of its fidelity to Montessori principles. This has resulted in substantial variation among schools calling themselves “Montessori,” from those with rigorous implementation and AMI/AMS-certified teachers to those that merely incorporate a few Montessori-inspired elements or materials. This inconsistency complicates research efforts, confuses parents, and sometimes leads to misunderstandings about what authentic Montessori education entails. The challenge of maintaining fidelity while allowing appropriate cultural adaptation remains an ongoing discussion within the Montessori community.

Criticisms from Traditional Educators

- Concern about transitions to conventional schools

- Questions about preparation for standardised assessments

- Perception of insufficient structure or academic rigour

- Skepticism about applicability to all learning styles

- Worries about competitive disadvantage in test-driven systems

Criticisms from Progressive Educators

- Perceived rigidity in material presentation

- Questions about cultural responsiveness and adaptation

- Concerns about prescriptive curriculum elements

- Debate about balance between freedom and structure

- Discussion of socioeconomic and cultural accessibility

The integration of Montessori education within mainstream educational systems presents complex challenges. Public Montessori programs must navigate tensions between Montessori principles and district or national requirements regarding standardised testing, curriculum coverage, and traditional assessment practices. Teachers in these settings often struggle to maintain Montessori fidelity while meeting external mandates, creating hybrid approaches that may compromise some Montessori elements. Additionally, the substantial difference between Montessori and conventional educational approaches can create transition challenges for students moving between systems, particularly if they enter conventional schools after several years in Montessori environments. While research indicates that Montessori students generally adapt successfully to conventional settings, concerns about these transitions remain a barrier for some families considering Montessori education.

Critical perspectives on Montessori come from both traditional and progressive educational viewpoints. Some traditional educators question whether Montessori’s emphasis on choice and intrinsic motivation adequately prepares children for conventional academic environments where external motivation and teacher-directed learning predominate. Conversely, some progressive educators critique aspects of Montessori they perceive as overly structured or prescriptive, particularly regarding the specified ways materials should be presented. These diverse critiques reflect genuine philosophical differences about education’s purposes and optimal methods, highlighting the ongoing dialogue about how best to support children’s development in a complex and changing world.

Conclusion: The Montessori Difference

The enduring significance of Montessori education lies in its profound respect for the child as a complete human being with inherent dignity and potential. While many educational approaches focus primarily on knowledge transmission or skill acquisition, Montessori addresses the development of the whole person—intellectual, physical, emotional, social, and spiritual. This comprehensive approach recognises that education is not merely preparation for future academic or professional success, but a process of supporting human development in its fullest sense. By trusting children’s natural drive to learn and grow, Montessori education cultivates not just academic capability but confidence, independence, and joy in learning that sustains individuals throughout their lives.

Central to the Montessori difference is its empowerment of children as active participants in their own development. Through carefully designed environments that allow for appropriate freedom, self-correction, and meaningful activity, children in Montessori settings experience themselves as capable, resourceful learners. Rather than depending on adults for direction and validation, they develop the ability to make choices, solve problems, and pursue interests with concentration and persistence. This sense of agency provides a foundation for lifelong learning, resilience in the face of challenges, and confidence in navigating new situations. As educational systems worldwide increasingly recognise the importance of these non-cognitive factors in determining life outcomes, Montessori’s century-long emphasis on developing such capabilities appears increasingly prescient.

Self-Actualisation

Fulfilling individual potential and purpose

Social Contribution

Participating meaningfully in community

Cognitive Development

Building knowledge and thinking skills

Practical Independence

Mastering self-care and life skills

Emotional Foundation

Developing self-regulation and resilience

The Montessori approach offers particular relevance in addressing contemporary educational challenges. As concerns about student engagement, mental health, and preparation for a rapidly changing future have intensified, Montessori’s emphasis on intrinsic motivation, self-regulation, and adaptable thinking provides a well-established alternative to test-driven, compliance-focused models. The methodology’s century-long track record of nurturing creative, independent thinkers who love learning offers a compelling vision of education aligned with human development rather than standardised outcomes. As we move further into the 21st century, Montessori’s influence continues to expand beyond dedicated Montessori schools, with its principles increasingly informing mainstream educational reform and practice.

Perhaps most fundamentally, Montessori education matters because it offers a vision of education as a transformative force for both individual fulfillment and social progress. Dr. Montessori believed that supporting children’s natural development toward independence, responsibility, and empathy could contribute to creating a more peaceful and just world. This vision of education as a path toward both personal and social transformation continues to inspire educators, parents, and communities seeking educational approaches that honour children’s humanity while preparing them to address the complex challenges of our shared future. In this sense, Montessori’s legacy extends far beyond specific classroom practices to encompass a profound respect for human potential and a belief in education’s power to positively shape individual lives and collective possibilities.

References

Association Montessori Internationale. (2023). Global diffusion of Montessori schools.

American Montessori Society. (2024). Fast facts: What is Montessori?

Frontiers in Developmental Psychology. (2025). Perfect timing: Sensitive periods for Montessori education and long-term well-being. Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 10, e1546451.

Lake Creek Montessori International School. (n.d.). Why Montessori. Retrieved May 2025

Lillard, A. S. (2017). Montessori: The science behind the genius (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Lillard, A. S., & Else-Quest, N. (2006). Evaluating Montessori education. Science, 313(5795), 1893-1894.

Lillard, A. S., Heise, M. J., Richey, E. M., Tong, X., & Hart, A. (2017). Montessori preschool elevates and equalizes child outcomes: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1783.

Lillard, A. S., Tong, X., & Snyder, A. L. (2022). Standardized test proficiency in public Montessori schools. Journal of School Choice, 16(1), 34-63.

Randolph, J. J., Bryson, A., Menon, L., Henderson, D. K., & Manuel, A. K. (2023). Montessori education’s impact on academic and non-academic outcomes: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 19(3), e1300.

Follow us on social media to stay updated on our latest updates and happenings:

Comments are closed