Introduction

Language is one of the most powerful tools children acquire in their earliest years. It is the medium through which they communicate needs, form relationships, and later, begin to read and write. For parents considering Montessori education, understanding how the method nurtures language development is vital. Unlike traditional models that focus heavily on direct instruction, Montessori education takes a holistic, child-centred approach. Language is absorbed, explored, and refined through a carefully designed environment and materials that align with a child’s natural growth.

The following article explores how Montessori education supports both monolingual and bilingual development. It draws on Dr Maria Montessori’s core principles, practical classroom practices, and modern research. By doing so, it highlights why Montessori remains a powerful framework for fostering literacy and communication in young children.

Section 1: Foundations of Language in Montessori

The Absorbent Mind and early language acquisition

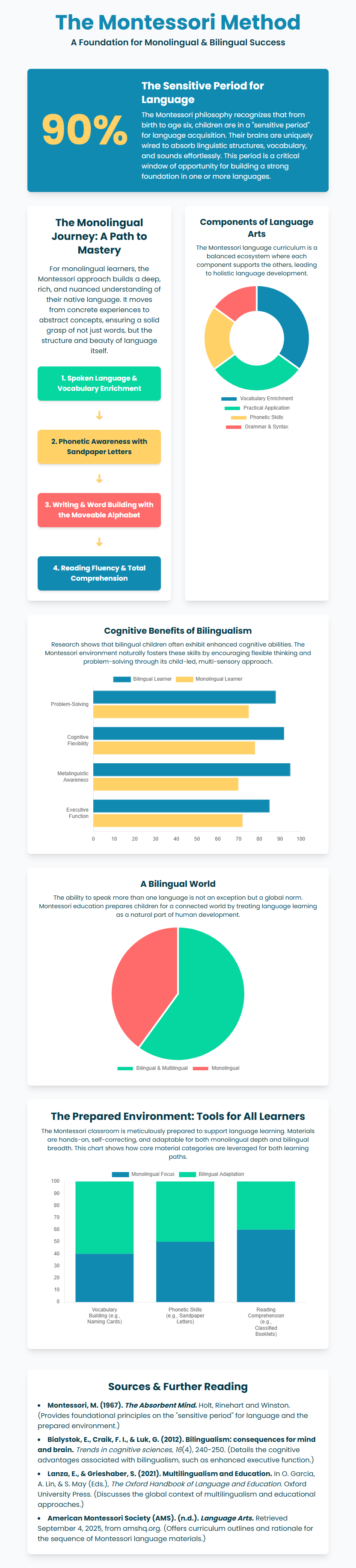

Central to Montessori education is the idea of the Absorbent Mind. Dr Montessori observed that from birth to around six years of age, children have a unique ability to take in their environment almost effortlessly. During this time, they absorb language sounds, sentence structures, and cultural norms without needing formal instruction. Unlike adults who rely on deliberate study, children at this stage soak in their surroundings naturally and build an internal framework for communication.

The Absorbent Mind has two phases. From birth to three years, the process is unconscious. Infants absorb sounds and rhythms simply by being exposed to them. Between three and six years, the process becomes conscious. Children start actively engaging with language, extending vocabulary, and experimenting with words. This natural capacity explains why Montessori schools place such emphasis on creating language-rich environments.

Sensitive Periods: windows of linguistic opportunity

Another key concept is the Sensitive Periods, which are specific stages in development where children are particularly receptive to acquiring certain skills. For language, the sensitive period is strongest from birth to six. During this time, children can acquire one or more languages with remarkable ease. If opportunities for exposure are missed, language learning is still possible later in life but requires much more effort.

Montessori educators pay close attention to these windows of opportunity. By observing children closely, they can introduce activities and materials when the child is most ready to benefit from them. This responsiveness ensures that the natural rhythm of development is respected and supported.

Auto-education: how children teach themselves language

Dr Montessori emphasised the principle of auto-education, meaning children are capable of teaching themselves when placed in the right environment. Rather than being passive recipients of information, children in Montessori classrooms take an active role in constructing knowledge.

Language activities are designed to be self-correcting. For example, the tactile feedback from Sandpaper Letters guides a child’s finger to form correct shapes. The material itself, rather than the teacher, provides feedback. This encourages independence and confidence, allowing children to discover the logic of language for themselves.

The Prepared Environment as a “third teacher”

The Montessori classroom is known as the Prepared Environment, and it functions almost like a third teacher. Every element of the space is designed with purpose, order, and accessibility. Low shelves, child-sized furniture, and neatly organised materials invite exploration and concentration.

In terms of language, the environment is filled with opportunities to hear, see, and practise words. Teachers, known as guides, model precise and respectful speech. Books are displayed attractively on low shelves to encourage independent reading. Objects may be labelled to connect written and spoken words. Even activities outside the language area, such as pouring water or polishing objects, indirectly prepare children for literacy by strengthening concentration, fine motor control, and sequencing skills.

Why the foundations matter

These three principles, the Absorbent Mind, Sensitive Periods, and auto-education combine with the Prepared Environment to create a strong base for language development. They explain why Montessori children are often able to progress naturally from spoken language to writing and reading without the resistance or anxiety sometimes found in traditional classrooms.

By recognising how children learn best, Montessori education makes language acquisition both joyful and effective. These foundations are not limited to monolingual contexts. They also create fertile ground for bilingual and even multilingual development, as we will see in later sections.

Section 2: Monolingual Language Development in Montessori

From sound to symbol: phonemic awareness and Sound Games

Montessori education begins language learning with spoken words rather than printed text. Before a child ever sees a letter, they are immersed in the sounds of language. Teachers engage children in conversations, read stories aloud, sing songs, and recite poems. This daily exposure builds a strong foundation of vocabulary and rhythm.

A key practice at this stage is the use of Sound Games, which help children develop phonemic awareness. In one common activity, the teacher might say, “I spy with my little eye something that starts with /m/.” The children then look around the room and guess objects such as “mat” or “mug.” These games are playful but purposeful. They train the ear to recognise individual sounds, an essential skill for later reading and spelling.

By focusing on sounds first, Montessori classrooms follow the natural order of human language development. Just as children learn to speak before they can write, they learn to hear and identify sounds before matching them to symbols.

Sandpaper Letters: multi-sensory pathways to literacy

Once children can identify individual sounds, they are introduced to the letters that represent them. Montessori uses a material called Sandpaper Letters. Each letter is cut from textured sandpaper and mounted on a wooden board. Vowels and consonants are colour coded to help children differentiate between them.

The teacher demonstrates by tracing the letter with two fingers while saying its sound aloud. The child then does the same, linking the sound with both a visual image and a physical sensation. This threefold approach, auditory, visual, and tactile creates strong memory pathways in the brain.

Children are introduced to letters in small groups, often chosen so they can quickly form simple words. For example, learning “c,” “a,” and “t” allows a child to write “cat.” This careful sequencing ensures early success and keeps motivation high.

The Movable Alphabet: writing before handwriting

One of Montessori’s most innovative contributions is the Movable Alphabet. This material consists of wooden or plastic letters stored in compartments. Children use the letters to build words and sentences on a mat, well before they are able to hold a pencil with control.

The Movable Alphabet removes the barrier of handwriting, which requires advanced fine motor skills. Instead, children can focus on the intellectual task of encoding sounds into symbols. For example, when presented with a toy dog, a child might analyse the sounds /d/, /o/, /g/ and then arrange the letters to spell “dog.”

This breakthrough often sparks what Montessori called an “explosion into writing.” Children become eager to form words and express their thoughts, realising they can put their ideas into symbolic form. They progress from simple words to phrases and eventually stories, all before mastering traditional penmanship.

Reading as discovery: the journey to “Total Reading”

In the Montessori sequence, reading comes after writing. Once children have used the Movable Alphabet to construct words, they are encouraged to read them aloud. The act of decoding is no longer a mystery. They already know the sounds and how they fit together, so reading becomes the natural next step.

At first, children match written labels to objects or pictures. Later, they read short sentences and phonetic booklets aligned with the words they have already built. This prevents frustration, as the material is always within reach of their current ability.

The ultimate goal is what Montessori called “Total Reading.” This is not just sounding out words but fully understanding meaning, structure, and expression. Grammar materials, such as colour-coded shapes representing different parts of speech, help children explore how language works. They learn that language is not only functional but also beautiful, opening doors to literature and creative expression.

Practical Life and Sensorial work as indirect preparation for literacy

Language development in Montessori is supported by all areas of the classroom, not just the language shelves. Practical Life activities, such as pouring water, spooning beans, or polishing silver, strengthen concentration, order, and fine motor control. These skills are essential for writing and reading. For example, carefully pouring liquid trains the same steady hand needed for controlling a pencil.

Sensorial activities also play an indirect role. Materials like the Knobbed Cylinders, which children lift using a three-finger grip, prepare the hand for holding a writing tool. Sound-based materials such as Sound Cylinders train auditory discrimination, which supports phonemic awareness. Even visual materials like the Pink Tower, which develops perception of size, sharpen the ability to distinguish between similar-looking letters such as “p” and “q.”

Why this sequential approach works

The monolingual Montessori language curriculum is structured to mirror the natural development of language in children. It starts with sound, moves to symbol, and then progresses to expression through writing, with reading as the culmination. Each step is carefully scaffolded so that children succeed without unnecessary stress.

Unlike conventional classrooms where writing and reading may feel like imposed tasks, Montessori children experience them as discoveries. They realise they already know the system because they have built it step by step. This builds confidence, independence, and a genuine love for language.

The focus on multi-sensory learning also ensures that different learning styles are supported. Whether a child learns best through movement, listening, or seeing, the materials engage multiple senses at once. This approach aligns with modern neuroscience, which shows that learning is strengthened when multiple pathways in the brain are activated.

Section 3: Social and Environmental Catalysts for Language

Mixed-age classrooms and authentic communication

One of the most distinctive features of Montessori education is the mixed-age classroom. Instead of grouping children strictly by year, Montessori environments bring together children across a three-year span. For example, a classroom may include children aged three to six. This arrangement is not accidental. It mirrors real-life communities where individuals of different ages interact, and it provides a powerful setting for language development.

Younger children benefit by being immersed in the conversations and activities of older peers. They absorb vocabulary and sentence structures that would not naturally occur in a group of children their own age. For instance, a four-year-old listening to a six-year-old explain how to use a material is exposed to more advanced language than a teacher-directed lesson might provide.

Older children also gain important benefits. When they help younger peers, they must simplify and clarify their own speech. Explaining how to trace a Sandpaper Letter or how to complete a Practical Life activity requires them to organise their thoughts and express them clearly. This process deepens their own mastery of language while fostering patience and empathy.

Peer-to-peer learning and vocabulary expansion

The social dynamics of a Montessori classroom create constant opportunities for peer-to-peer learning. Children naturally engage in discussions as they share materials, collaborate on projects, or resolve conflicts. These interactions go beyond academic tasks and extend into practical communication skills such as negotiation, persuasion, and storytelling.

Because children work independently or in small groups rather than as a whole class directed by a teacher, the language exchanged is authentic. It arises from genuine needs and interests, making it far more meaningful than scripted dialogues. Whether a child is asking for help, offering an explanation, or narrating a discovery, the language is purposeful and rooted in real experience.

This authenticity accelerates vocabulary growth. Words are not memorised from a list but are encountered in context. A child learns the meaning of “cylinder” by physically handling one in the Sensorial area, hearing a peer describe it, and later reading its label. This layered exposure ensures a deeper and more lasting understanding.

The guide’s role: facilitating, not instructing

In the Montessori environment, teachers are known as guides. Their primary responsibility is to connect children with the materials and the environment rather than to deliver lectures. This shift in role has profound effects on language development.

Guides model clear, precise, and respectful language at all times. They avoid unnecessary baby talk or oversimplification, trusting children to absorb sophisticated vocabulary. For example, rather than saying “a big block,” a guide might say “a large cube.” This subtle difference gradually enriches the child’s vocabulary and sets a high standard for communication.

The guide also uses one-to-one or small-group lessons, which allow for more personalised dialogue. Unlike traditional classrooms where a teacher speaks to thirty children at once, Montessori lessons are intimate and conversational. This structure encourages children to ask questions, repeat phrases, and engage actively in the exchange rather than passively listening.

Another important role of the guide is observation. By carefully watching each child, the guide identifies signs of readiness for new language experiences. For example, noticing a child’s growing interest in letter sounds may prompt an introduction to Sandpaper Letters. This responsiveness ensures that each child is challenged appropriately without being overwhelmed.

Building a culture of communication

The social and environmental features of the Montessori classroom work together to create a culture where language is both functional and valued. Mixed ages encourage natural mentoring, peer interactions promote authentic dialogue, and the guide’s careful modelling sets a high standard.

Over time, children come to see language not as an academic subject but as a living tool for connection and expression. They learn that words can help them share ideas, solve problems, and build friendships. This perspective nurtures not only literacy but also social confidence and emotional intelligence.

Why environment matters as much as materials

While the iconic Montessori materials like the Movable Alphabet often receive attention, it is important to recognise that the environment itself is just as influential. A beautifully ordered, respectful, and socially dynamic classroom provides the context in which materials come alive. Without this environment, language learning would be far less effective.

Montessori education demonstrates that children do not acquire language in isolation. They learn it in community, through relationships, and within a setting that values communication. This understanding bridges directly into bilingual and multilingual contexts, where the same principles can be applied to foster competence in more than one language.

Section 4: Montessori and Bilingual Development

Why Montessori is ideal for bilingualism

The same principles that make Montessori so effective for monolingual language development also support bilingual and even multilingual growth. Dr Montessori observed that the Absorbent Mind is not language-specific. Children under six can absorb multiple languages in parallel, provided they are exposed to consistent and meaningful input. In other words, a child does not “learn a second language” in the way an adult does. They acquire languages naturally as part of their environment.

Research has shown that bilingualism in early childhood offers lasting benefits. It enhances executive functioning skills such as problem-solving, attention control, and cognitive flexibility. Montessori classrooms, with their multi-sensory approach and emphasis on self-directed exploration, provide an ideal structure for this natural bilingual acquisition. By combining rich input with purposeful activities, children gain fluency in two languages without feeling overwhelmed.

Immersion models: OPOL, Time and Place, and home support

Bilingual Montessori programmes often adopt clear models to provide structured exposure. One of the most common is the One Person, One Language (OPOL) approach. In this model, one guide consistently speaks English while another speaks the partner language, such as Mandarin. This clarity helps children categorise and process the languages as distinct systems. It avoids confusion and ensures that each language receives consistent, high-quality input.

Another approach is Time and Place (T&P), where languages are separated by schedule or location. For instance, the morning may be conducted in English, while the afternoon lessons are in Mandarin. Alternatively, specific areas of the classroom can be designated for each language. While effective, this model requires careful planning to maintain consistency.

Families can also contribute through the Minority Language at Home (MLAH) strategy. Parents speak the less dominant language at home, while the child is immersed in English at school. When combined with Montessori’s prepared environment, this approach reinforces both languages and creates balance between home and school experiences.

A thoughtful example of how Montessori supports bilingual growth can be seen in the way classified cards are used. These cards, which feature pictures and corresponding labels, can be produced in two languages. A child may sort objects by matching the English word to its picture, and later repeat the activity using Mandarin labels. This reinforces vocabulary across languages while keeping the activity engaging and hands-on.

Bilingual materials and cultural integration

Montessori materials are highly adaptable for bilingual learning. Sandpaper Letters and the Movable Alphabet, for instance, can be prepared in two languages. This enables children to explore phonetic differences and letter-sound relationships in each language. Because the method is rooted in sensory experience, the transition between languages feels natural rather than forced.

The classroom environment is also enriched with bilingual resources. Books are available in both languages, and everyday objects are often labelled with dual-language cards. This ensures that children encounter print consistently across contexts. For example, a chair might have a label reading “chair” in black text and “椅子” in red text, providing a constant, passive exposure to both written systems.

Cultural integration is equally important. Montessori classrooms do not present language in isolation but embed it within real-world experiences. Celebrations of cultural festivals, songs, storytelling, food preparation, and art projects all provide authentic contexts for using each language. This approach fosters not only bilingualism but also biculturalism. Children learn that language is tied to culture and identity, giving them a richer and more meaningful understanding.

An article by Montessori Oaks highlights that bilingual Montessori environments encourage children to see languages as “keys that unlock different ways of seeing the world” (Montessori Oaks). This perspective moves beyond mechanics to cultivate empathy, respect, and curiosity for other cultures.

Biculturalism and global awareness through Montessori

One of the long-term goals of Montessori education is to prepare children to be global citizens. Bilingual programmes are particularly well suited to this aim. By exposing children to more than one language and culture from the beginning, they gain not only communicative skills but also intercultural sensitivity.

For example, a child who celebrates Lunar New Year in Mandarin while also reading English storybooks develops a sense of belonging in both cultural worlds. This dual identity strengthens confidence and nurtures flexibility. It also prepares children to thrive in increasingly interconnected societies where bilingualism is a practical advantage.

Montessori philosophy naturally aligns with this vision. Its respect for the child, emphasis on peace education, and celebration of cultural diversity provide fertile ground for developing not just bilingual learners but also compassionate, globally minded individuals.

Why consistency matters in bilingual Montessori programmes

The success of any bilingual Montessori programme depends on consistency. Children rely on order and predictability to make sense of their environment. If adults frequently switch between languages without clear structure, it can lead to confusion. Consistent models such as OPOL or T&P ensure that children receive reliable input.

The role of the guide is crucial here. They must not only be fluent but also model rich, expressive language. Training and professional development in bilingual education strategies ensure that the classroom maintains fidelity to both Montessori principles and language immersion goals.

Parents also play an important role. When families reinforce language learning at home through books, conversations, or cultural experiences, children receive more balanced exposure. The partnership between home and school strengthens both languages and ensures long-term success.

Section 5: Evidence and Research on Outcomes

Meta-analyses on Montessori and literacy

For many parents, choosing a preschool is as much about evidence as philosophy. Over the last two decades, a growing body of research has evaluated Montessori education, particularly its impact on language and literacy. Some of the strongest findings come from large-scale meta-analyses.

A comprehensive review published by the Campbell Collaboration analysed more than thirty experimental and quasi-experimental studies. The results showed consistent, positive effects for Montessori students across academic, social-emotional, and cognitive domains, with especially clear advantages in literacy. The authors concluded that Montessori has “strong and clear effects” on reading and writing development, particularly when programmes are implemented with fidelity (K12 Dive).

Another independent review reached similar conclusions, highlighting not only gains in early literacy but also broader benefits such as executive function. This growing consensus moves the Montessori conversation beyond anecdote, placing it firmly within evidence-based practice.

Key studies versus conventional programmes

Individual studies also shed light on the unique strengths of Montessori language education. A landmark investigation by Angeline Lillard compared children randomly assigned to a public Montessori programme with peers in conventional classrooms. By age five, the Montessori group showed significantly stronger phonological awareness and early reading skills. By age twelve, they demonstrated more advanced sentence structure and creativity in writing.

More recent work continues to confirm these advantages. A 2021 study found that children aged four to six in Montessori environments made significant progress in phonological awareness and print awareness, both of which are crucial precursors to fluent reading (ResearchGate).

For parents concerned about whether Montessori children “fall behind” because they learn differently, these studies provide reassurance. Not only do Montessori pupils keep pace, but in many cases they exceed the literacy outcomes of peers in more traditional settings.

Findings from bilingual Montessori programmes

The research base on bilingual Montessori programmes is smaller but equally promising. One study of Latino preschool children compared those enrolled in a bilingual Montessori programme with peers in transitional bilingual classrooms. The Montessori group outperformed the comparison group on reading assessments in both Spanish and English. This suggests that Montessori not only supports biliteracy but also strengthens the home language while fostering English proficiency.

Other case studies show similar results. At schools using dual-language immersion models, children demonstrate strong outcomes in both languages without sacrificing one for the other. The emphasis on phonemic awareness, hands-on exploration, and multi-sensory materials seems to provide a transferable advantage across languages.

Educators note that children in bilingual Montessori settings often display high levels of confidence when switching between languages. This may be because the method treats each language as a complete, coherent system rather than as a subject taught in isolation. As a result, children develop balanced bilingualism and cultural awareness simultaneously.

The fidelity challenge: why implementation quality matters

While the evidence is encouraging, researchers caution that outcomes depend heavily on implementation. The term “Montessori” is not trademarked, and schools vary widely in how faithfully they follow the method. High-quality programmes include fully trained guides, complete sets of materials, mixed-age groups, and uninterrupted three-hour work cycles. When any of these elements are missing, results can be diluted.

Studies that account for fidelity show the strongest outcomes. For example, high-fidelity classrooms are associated with greater gains in vocabulary, reading comprehension, and executive function compared to both conventional schools and lower-fidelity Montessori programmes. This finding underscores the importance of parents asking not only whether a school calls itself Montessori but also whether it truly follows the philosophy.

An article by Montessori Public Works explains that implementation quality is the single most important predictor of success. Schools that invest in teacher training and protect the integrity of the work cycle consistently see better academic and social outcomes (Montessori Public Works).

Why research matters to families

For families, the practical question is whether Montessori will prepare their child for future academic demands. The research increasingly suggests that it does. Children who begin their educational journey in Montessori settings often enter primary school with strong phonics skills, confidence in writing, and a love of reading.

Moreover, bilingual programmes add another dimension. They allow children to maintain or develop an additional language while meeting or surpassing benchmarks in English. In a multicultural society, this is a valuable advantage.

At the same time, parents should recognise that Montessori is not a shortcut or a gimmick. Its effectiveness depends on the quality of the environment, the training of guides, and the consistency of practice. Visiting classrooms, asking questions about daily routines, and observing how children engage with materials are important steps in choosing the right school.

Section 6: Montessori vs Traditional Language Education

Philosophical differences in language teaching

At the heart of the difference between Montessori and traditional education is philosophy. Montessori sees the child as an active agent in their own development. Language is discovered through exploration, play, and interaction with carefully prepared materials. Traditional classrooms, by contrast, often treat language as a subject to be taught by direct instruction, with teachers leading the process and children following.

In Montessori, learning is child-centred and individualised. Each child progresses at their own pace, choosing materials based on interest and readiness. In conventional classrooms, learning is standardised, with the whole class expected to move through a set curriculum at the same speed. This distinction shapes not only the classroom atmosphere but also how children experience language itself.

Montessori and the “Science of Reading”

In recent years, the Science of Reading movement has gained attention, advocating for structured and explicit phonics instruction. Some critics question whether Montessori, which introduces sounds and letters through hands-on materials, aligns fully with this evidence.

Montessori in fact offers a systematic approach to phonics. Children play Sound Games to isolate phonemes, trace Sandpaper Letters to connect sound with symbol, and use the Movable Alphabet to encode words. This sequence provides explicit practice, though it looks different from worksheets or drill-based instruction.

Still, some programmes have been criticised for inconsistencies in sequencing. For example, a review by Rhyme and Reason Academy points out that some Montessori schools introduce complex phonograms earlier than necessary, potentially causing confusion (Rhyme and Reason Academy). These critiques highlight the importance of maintaining clarity and aligning practice with current literacy science while retaining Montessori’s multi-sensory foundation.

Strengths of Montessori language programmes

Despite the critiques, Montessori has distinctive strengths. Its emphasis on writing before reading allows children to express themselves without being held back by motor skills. Materials are self-correcting, which reduces pressure and builds independence. The environment integrates indirect preparation for literacy, meaning that fine motor skills, concentration, and sequencing are developed naturally before formal reading.

Montessori also avoids the stress of standardised testing at early ages. Errors are treated as opportunities to learn rather than failures. This builds resilience and encourages children to take risks with language, fostering creativity alongside accuracy.

Another strength is the way Montessori integrates language into everyday life. Vocabulary is not learned from lists but encountered through purposeful activities. For instance, a child learns the word “polish” while polishing brass or “cylinder” while working with Sensorial materials. This contextualised learning makes vocabulary richer and more meaningful.

Critiques and perceived limitations

Like any method, Montessori is not without challenges. One common critique is that the emphasis on independent work may limit opportunities for collaborative group projects, which are often valued in modern education for developing teamwork skills. While Montessori classrooms encourage peer learning, some observers argue that structured group activities are less frequent.

Another challenge is variability. Because the Montessori name is not protected, quality differs widely across schools. Some institutions use the label without providing full training or proper materials. Families need to research carefully to ensure they are choosing a school that follows high-fidelity practices.

Cost is also a factor. Montessori schools often operate as private institutions with higher fees than public options. While subsidies or partner-operator models may exist in some regions, access remains unequal. This has led to debates about whether Montessori can be scaled equitably.

An article from Our Kids explains that critics often highlight these barriers, yet also acknowledges that most limitations arise from implementation rather than philosophy itself (Our Kids). When executed with fidelity, Montessori has shown consistently positive outcomes.

Striking a balance between tradition and innovation

The comparison between Montessori and traditional methods need not be framed as a battle. Both approaches have insights to offer. The challenge for educators is to balance Montessori’s respect for the child’s natural rhythm with the structured insights of modern cognitive science.

For instance, Montessori could strengthen its sequence of phonics instruction by adopting more systematic guidelines while retaining the tactile and sensory richness of its materials. Traditional schools, on the other hand, might draw inspiration from Montessori’s prepared environments, valuing hands-on exploration rather than relying solely on worksheets.

Ultimately, parents and educators benefit from seeing these methods in dialogue rather than opposition. Montessori offers a holistic and joyful approach to literacy, while the Science of Reading brings evidence-based rigour. Together, they can help shape a generation of confident and competent readers.

Section 7: Recommendations and Future Directions

High-fidelity practices for language education

The research is clear: Montessori’s benefits for language are strongest when the philosophy is implemented consistently. For families and educators, this means protecting the essential features of the method. One of the most important is the uninterrupted work cycle, where children have long stretches of time to choose, explore, and concentrate on their tasks. This period allows for deep engagement with language materials such as the Movable Alphabet or early reading cards.

Another key practice is ensuring that the full sequence of language materials is available and well maintained. From Sound Games to Sandpaper Letters, each step in the sequence builds on the one before. Skipping or diluting materials reduces the coherence of the system. Classrooms should be carefully prepared, attractive, and orderly so that children can take ownership of their learning.

At Starshine Montessori, for example, teachers focus not only on providing high-quality materials but also on creating an environment where children feel empowered to explore language at their own pace. This commitment to detail ensures that children’s early literacy journey is joyful, natural, and effective.

Strengthening bilingual programmes with consistent input

For schools and families interested in bilingual development, consistency is essential. Children thrive when each language has a clear role in their daily life. In Montessori classrooms, this can be achieved through models like One Person, One Language, where each guide speaks only one language, or through careful scheduling of language times.

Equally important is cultural integration. Celebrating festivals, reading stories, and singing songs in both languages helps children connect language to identity. This prevents bilingualism from feeling like an academic exercise and instead roots it in real experiences.

Starshine Montessori’s bilingual environment reflects this philosophy. Children encounter English and Mandarin daily, not only in structured lessons but also in songs, celebrations, and daily conversations. This approach nurtures fluency in both languages while fostering respect for cultural diversity.

Integrating modern linguistic research with Montessori principles

While Montessori education is over a century old, it remains strikingly relevant. However, there is room to refine its practices in light of modern linguistic research. The Science of Reading emphasises systematic phonics instruction, and Montessori can strengthen its alignment by ensuring clear, logical sequencing of sound-letter introductions. This does not mean abandoning the multi-sensory approach but rather complementing it with careful attention to order and progression.

Montessori classrooms can also enhance opportunities for oral language production, particularly in bilingual programmes. While many activities involve listening and vocabulary building, structured peer-to-peer tasks can encourage children to use both languages more actively. Research on task-based language learning suggests that collaborative activities increase oral fluency. These could be adapted into Montessori environments in ways that preserve independence and choice while promoting dialogue.

Future research directions

Although Montessori has a strong evidence base, further research is needed to address specific questions. Longitudinal studies following children from preschool into secondary school could provide valuable insights into how early Montessori language experiences affect long-term literacy. Research into bilingual Montessori programmes, particularly in multicultural settings like Singapore, would also help clarify best practices for biliteracy.

Another promising area is the study of Montessori’s effectiveness for children with speech or language delays. The multi-sensory, individualised nature of the method suggests it could be particularly beneficial, but more formal studies are required to confirm this potential.

Why this matters for families

For parents, the practical question is not only whether Montessori works, but whether it works in the specific school they are considering. Looking for signs of fidelity, such as mixed-age classrooms, uninterrupted work cycles, and complete sets of materials, helps ensure that the philosophy is being followed authentically.

Equally, observing how children interact with language in the classroom can be revealing. Do they have opportunities to speak, write, and read at their own pace? Are they enthusiastic about using language to explore ideas and express themselves?

Starshine Montessori offers parents reassurance in this regard. With its commitment to both monolingual and bilingual development, and its focus on creating a prepared environment that celebrates independence and cultural diversity, it embodies the principles that research has shown to be effective. For families seeking a preschool that blends academic preparation with a love for language, Starshine provides a living example of Montessori at its best.

Conclusion

Montessori education offers a coherent and powerful framework for early language development. From the Absorbent Mind and Sensitive Periods to the carefully sequenced materials like Sandpaper Letters and the Movable Alphabet, its design is both logical and child-centred. For monolingual children, this means moving naturally from sound to writing and finally to reading with confidence. For bilingual learners, it provides fertile ground for acquiring two languages simultaneously, grounding them in both cultural identity and global awareness.

Research has confirmed what Dr Maria Montessori observed more than a century ago: when implemented faithfully, the method leads to strong literacy outcomes. Children not only meet academic benchmarks but often exceed them, showing creativity, independence, and enthusiasm for communication.

At Starshine Montessori, these principles are alive in daily practice. Through bilingual immersion, rich cultural integration, and an unwavering focus on the prepared environment, children gain the skills and confidence they need for lifelong learning. For parents seeking a preschool that nurtures both the mind and the spirit, Starshine offers a clear choice rooted in evidence and guided by respect for the child.

FAQs

What makes Montessori different from traditional phonics teaching?

Montessori introduces phonics through multi-sensory materials rather than worksheets. Children trace Sandpaper Letters while saying the sounds, use Sound Games to isolate phonemes, and build words with the Movable Alphabet. This hands-on sequence ensures that sounds are mastered in a concrete, engaging way.

Can children learn two languages at once in Montessori?

Yes. The Absorbent Mind allows children under six to acquire multiple languages effortlessly if the environment is consistent. Montessori bilingual classrooms often use the One Person, One Language model, where each guide speaks only one language. This provides clarity and rich input in both languages.

At what age do Montessori children start with language materials?

Spoken language activities begin as soon as a child joins the classroom. Formal phonics work with Sandpaper Letters usually begins around age four, when children show readiness. By then, they already have strong phonemic awareness built through songs, stories, and Sound Games.

Is Montessori effective for children with speech or language delays?

The individualised, multi-sensory approach is well suited to children with speech or language challenges. Materials provide self-correction and remove pressure, allowing children to progress at their own pace. While more research is needed, many parents and therapists have found Montessori supportive for diverse learners.

How does bilingual Montessori prepare children for future schooling?

By integrating two languages into daily life, bilingual Montessori programmes develop balanced biliteracy. Children leave with confidence in both speaking and reading, alongside cultural awareness. These skills not only prepare them academically but also give them a strong foundation for thriving in multilingual societies.

References

- The Absorbent Mind | West Side Montessori – Toledo West Side Montessori

- Key Montessori Principles of Education Montessori Academy

- Language in the Early Years Kinderhouse Montessori

- Montessori Letters: Using Sandpaper Letters & the Moveable Alphabet The Montessori Site

- Montessori Material of the Month: The Movable Alphabet Unionville College

- Empowering Young Minds with the Montessori Movable Alphabet Montessori Academy

- How Montessori Education Supports Language and Bilingual Development Starshine Montessori

- The Benefits of Bilingual Education: Montessori’s Approach to Language Learning Montessori Oaks

- Montessori And Bilingualism: A Perfect Pair For Early Education Excelled Schools

- Montessori method has strong and clear impact on student outcomes K12 Dive

- The effect of Montessori education on the development of phonological awareness and print awareness ResearchGate

- Research + Outcomes Montessori Public Works

- A Brutally Honest Review of Montessori Reading Programmes Rhyme and Reason Academy

- Montessori criticisms, problems, and disadvantages Our Kids

Follow us on social media to stay updated on our latest updates and happenings:

Comments are closed